Before I became a writer, I was a musician. I started piano lessons, not by choice, at age nine. I went through three different teachers in as many years. I dreaded lessons and practice. I dreaded the cheesy pop songs, the sheet music for which my mother would pick out for me to play. I dreaded my first recital because my mom had made me dress up in “good” clothes, and I was afraid of making a mistake. I think my mom wanted me to study piano because she was really the one who wanted to learn.

When I was eleven, I saw an article in the local newspaper that featured a nearby drum and bugle corps: the Guardsmen. I showed it to my mom, and to my disbelief, when I asked if I could join she said yes. I promptly quit piano lessons. She allowed me to sign up for the Guardsmen Cadets, whose members were between the ages of eight and thirteen. They were the junior version of the Guardsmen Drum and Bugle Corps.

The instructors decided that I would play the snare drum, which apparently, is the most challenging instrument on the drum line. I don’t know why, because I had never picked up a pair of drumsticks before but I think it’s because I was a small child and that instrument didn’t weigh as much as the other drums.

The Cadets wore bright orange tunics over black pants and shoes. Our helmets were white, and had front and rear visors like Sherlock Holmes’s hat but smaller. A short pole was affixed to the top, and fake white hair resembling a horse’s tail cascaded down so the ends lightly brushed the helmet. We marched in parades in the suburbs, like on the Fourth of July and Saint Patrick’s Day.

When I aged out of corps at fourteen, I joined the high school marching band. At summer band camp, which consisted of practicing every single day for a week, we drank lots of water and wore sun hats and complained to one another about the heat. Some members loved the band director, but I thought he was a bully. I was promised a spot on the snare line before camp started, but it didn’t happen. I ended up playing the bass drum, which is awkward to carry. They were large instruments, the side of which was strapped to my front. I could hardly see over it. Anyway, the director seemed to get extreme joy out of nitpicking me in front of the entire band, as though it would delight him if I broke down and cried. I never did.

In the fall, I enrolled in the Concert Band, which counted as a class. I didn’t realize we had juries, which was the equivalent of an exam. It was you, by yourself, playing a solo written for your instrument in front of the rest of the band. When it was my turn, I performed a piece on the snare drum (of course) that I worked hard on all of fall term. After I hit the last note, the band director turned to me and asked, “You call that music?” He gave a short dispatch on why it wasn’t music, but all I could hear was, you call that music, you call that music, you call that music? My throat was dry as a snake’s skin after it’s been shed. I got a C—a first in my academic career.

I managed to make it through my sophomore year, but was increasingly uncomfortable in the practice room. The director’s mere presence triggered heat that slowly rose up my face and neck and especially when he glanced my way. I was afraid he’d make a snarky comment about me or to me.

Later that year, my mom showed me a newspaper article about a Chicago arts high school like the one in the movie Fame. Prospective students had to audition to be accepted, and I was, having played a piece on the snare drum. So take that, Mr. Band Director. Maybe I could play music after all; the admissions committee seemed to think so. In the fall of 1985 when I was a junior, I transferred and focused on music and not so much on academics anymore. We studied subjects such as music theory and music history.

In 1989, I was awarded a partial scholarship to attend the University of Houston. Because I wanted to be a music performance major—a percussionist—I had to audition with the snare drum and other percussion instruments like the tympani, marimbas, and xylophone. Piano lessons were useful after all, in terms of playing the latter two. My dream was to play in a professional orchestra. (My other dream was to become a rock star.)

I had difficulty adjusting to college because the place was huge. There were only fifty students in my high school graduating class and at least a hundred in the lecture hall for an English class. I was used to individualized attention. I especially had difficulty in my department because I was the only woman. Only two other percussion students talked to me. One was a freshman like me; the other was a junior who was kind. I had wanted to play in the marching band, but was sadly too intimidated.

I dropped out, not just because of that, but also because I experienced suicidal thoughts for the first time. I considered overdosing on something because that seemed the least violent way to die. Cutting myself made a mess and I didn’t want that for my roommate. I couldn’t figure out how to tie a noose. Instead, I called my parents and asked for help. They promised they would get it for me, but didn’t follow through. I wasn’t diagnosed with bipolar disorder until a few years later. They did, however, move me back to Chicago.

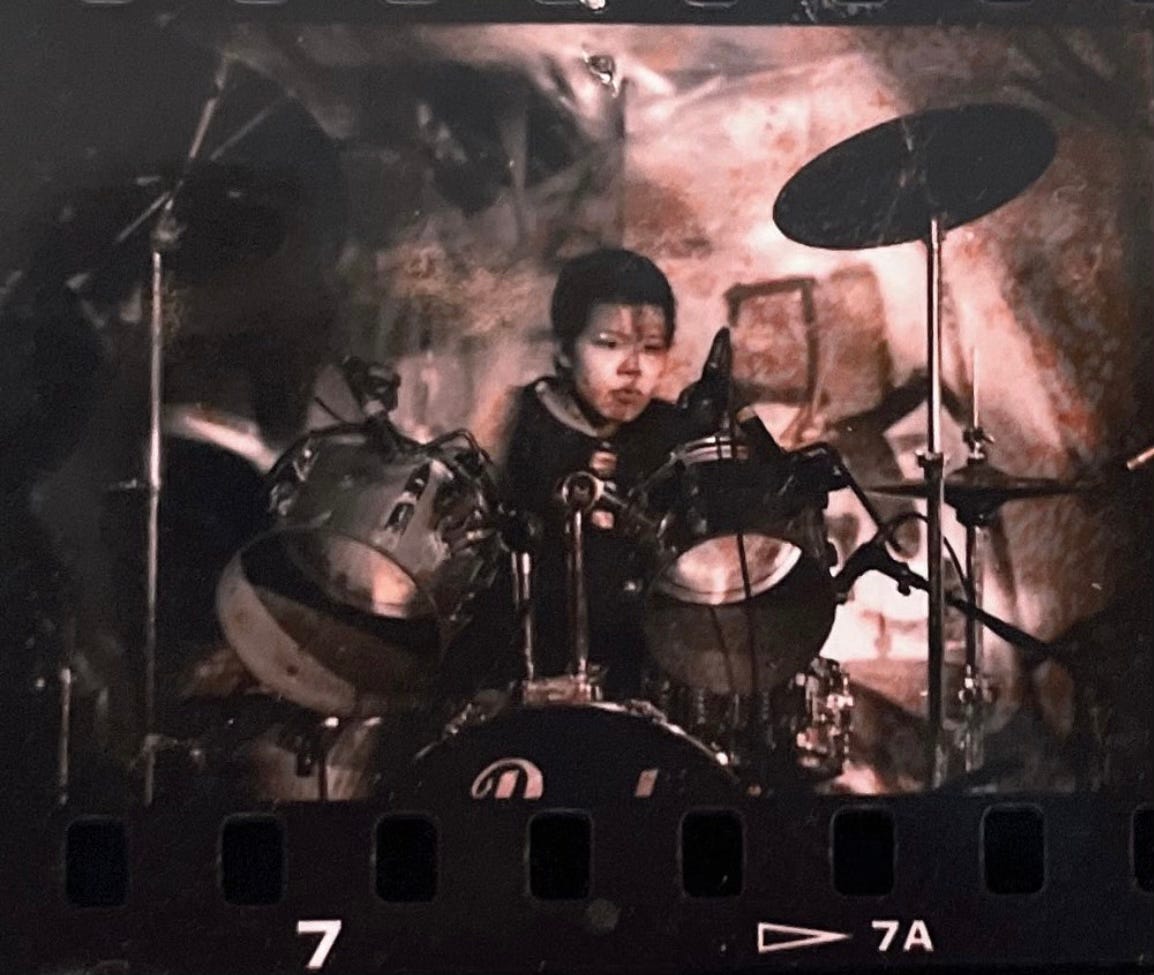

After I returned, I started playing in rock bands again, which I’d done since I was fifteen. This time, the bands I played in actually had gigs, maybe because we were older than twenty-one and could enter the concert venues legally. I was always the only woman, and I think the other band members thought of me as “one of the guys.” Despite working full-time as a secretary, music was my lifestyle.

The audio file below was one of the songs on our demo tape. It starts five seconds in. The band was called Crash Curtain; the song is “Ivan the Terrible” (J. Blum, J. Porterfield, B. Natividad). The singer/bass player would later become my first husband but that’s another story.

When I was twenty-five, I was supposed to replace the drummer for a band on an indie record label, for the second leg of their tour. They were popular in Chicago and had a song that was constantly played on the radio. I learned all their songs even though I never had the chance to practice with them. When I hadn’t heard from them in weeks, I finally called one of the band members who said, “Management says it’s too early in our career for a personnel change.” I was shocked by the corporate-sounding statement, and was devastated because I wouldn’t be going on tour. It took years for me to get their songs out of my head. I felt my music career had come to an end.

I no longer wanted to be a secretary, which was my day job, so I decided to go back to school—to a small college. I was a biology major with the intention of applying to veterinary schools after graduation. Well, math and science were never my strongest subjects. However, I could read so I became an English major. That’s when I began writing.

Comedy, Tragedy is a free publication. But if you enjoyed this post, you can tell Barb that her writing is valuable by buying her an almond milk cappuccino so she can head to the coffee shop and write more content. Thank you!

Love reading this backstory!

Barb, I feel like you've lived so many lives in this lifetime! I look forward to knowing about all the chapters of it you are willing to share. Reading Comedy, Tragedy is like having you over for a sleepover and just talking about life--really, that's what it feels like to me.